The 1969 Chevrolet Camaro COPO ZL1. (Photo courtesy of Barrett-Jackson.)

Not unlike Plymouth’s Barracuda and Dodge’s Challenger, the Camaro’s genesis resulted from Ford’s meteoric success with the release of the 1964 ½ Mustang. As was the case with Chrysler, General Motors realized that the Mustang had heralded an entirely new sector of the automotive market – the pony car – and sought to cash in on it with a model of their own.

News of GM’s plans to produce a pony car, code-named Panther, began to leak to the automotive press as early as the spring of 1965. Just over a year later, Chevy held a press conference in Detroit in which the launch date was revealed. The Chevrolet “Camaro” would begin prowling the streets and highways of America in the fall of 1966.

A clay design model of the Chevrolet “Panther.” (Photo courtesy of General Motors Media Archive.)

Many immediately wondered exactly what a “Camaro” was. The answer varied wildly depending on who you asked. Chevrolet General Manager, Pete Estes, claimed that the name referred to “the comradeship of good friends, as that is what a personal car should be to its owner. To us, the name means just what we think the car will do… go.” Others had more grounded answers. Some claimed it was French slang for “buddy,” while several in the automotive press were told that it was “a small, vicious animal that eats Mustangs.”

The public introduction of the 1967 Camaro occurred on September 26th, 1966, and what a car it was. A sleek and compact-looking 2+2 that rode on the front-engine, rear-wheel-drive GM F-body chassis, the Camaro was available in two-door coupe and convertible styles. Sharing some mechanicals with the forthcoming 1968 Nova, the Camaro utilized a unibody structure, combined with a subframe supporting the front end.

A vintage advertisement for the 1967 Chevrolet Camaro. (Image courtesy of General Motors Media Archive.)

A masterpiece of design, the car had similar long hood/short deck proportions to the Mustang and featured a deeply recessed grille with headlights in the corners, sensuous hips above the rear wheel arches, and an elegant, no-frills silhouette.

Motivation consisted of a choice between 230 and 250 cubic inch inline-sixes, or 302, 307, 327, 350, and 396 cubic-inch V8 lumps. Available transmissions included a Muncie four-speed manual as standard, with a two-speed Powerglide and three-speed Turbo-Hydramatic 350 available.

A 1967 Camaro with the RS package. Note the covered headlights and unique rocker trim. (Photo courtesy of Mecum Auctions.)

Nearly 80 factory options were available, including three main packages. The RS group was an aesthetic package that included hidden headlights, revised taillights, unique rocker trim, and RS badging.

The SS package gave you the 350 cubic-inch V8, with the L35 396 available for an upcharge. Non-functional hood air intakes were also included, as was special striping and SS badging on the grille, gas cap, and horn button. The SS package could be combined with the RS to yield a Camaro SS/RS.

A 1967 Chevrolet Camaro in SS trim. (Photo courtesy of Bringatrailer.com.)

The third main package was the high-performance Z/28 option. Only available by ordering a base model Camaro, it brought a 302 cubic inch small-block with Corvette-sourced heads, a hot cam, solid lifters, a baffled oil pan, and a Holley four-barrel atop an aluminum manifold to the proceedings. Factory rated at 290 horsepower, the 302 was actually putting out between 360 to 400 ponies.

A 1967 RS Z/28. (Photo courtesy of GM Authority.)

Other niceties in the Z/28 package included the F41 handling suspension, 15-inch tires on 6-inch Rally wheels, and quick-ratio manual steering. A Muncie four-speed was the only transmission available in the Z/28, and power front disc brakes were a mandatory option.

GM hit a sweet spot with the Camaro’s looks, performance, and available options, and as such, sales were brisk, if not nearly on par with the number of Mustangs rolling off the line. In fact, 220,906 Camaros nonetheless found new homes in the 1967 model year.

The first-generation Camaro would continue until the end of the 1969 model year, with changes limited to small trim items such as the addition of side marker lights, rear quarter panel gills, and differing bumper trim.

During its run, sales of the first-gen continued to lag behind the Mustang, and more competition in the form of the E-body Challengers and Barracudas came in 1969 as 1970 models. What’s more, while Camaro’s high-performance engine choices remained the same, Ford began to offer powerplants in the ‘Stang, such as the big-block in the Boss 429, that Chevy had no answer for.

This was the result of an edict General Motors imposed on its divisions at the time that no engine larger than 400 cubic inches could be installed in anything less than a full-size car (with the Corvette being the lone exception.). The policy upset many in the dragstrip and Chevy enthusiast communities, who were losing heart watching Ford and Chrysler eat their lunch for them.

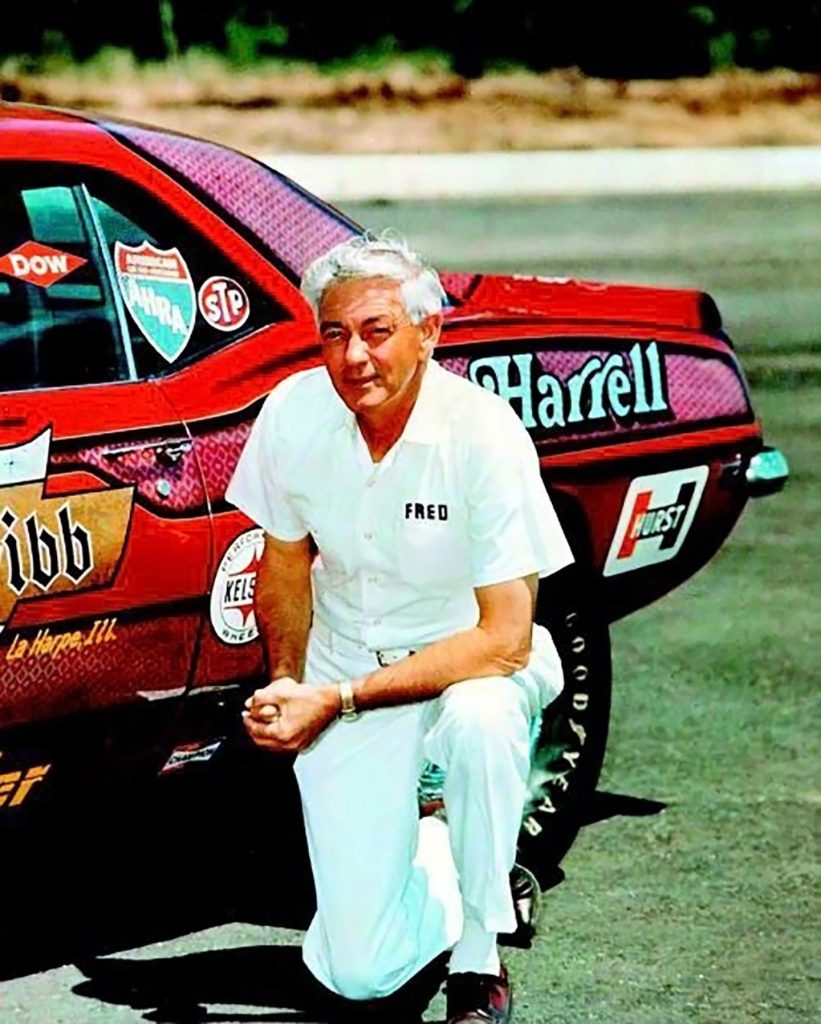

Chevy dealer and driving force behind the Camaro COPO ZL1, Fred Gibb. (Photo courtesy of Hemmings News.)

Two such figures were Fred Gibb and Chevy drag racer, Dick Harrell. Owner of Gibb Chevrolet in La Harpe, Illinois, Gibb had, for several years, been producing low volume cars for Harrell’s use at the drag strip by exploiting a little-known loophole in the Chevrolet factory order process.

COPO, short for Central Office Production Order, was a process that enabled custom vehicles to be special-ordered directly from the factory. Originally intended for the production of vehicles to supply the needs of taxi and fleet customers, it enabled unique liveries and heavy-duty components to be added to any vehicle in the Chevrolet roster.

Drag racer Dick Harrell. (Photo courtesy of Hemmings News.)

Gibb and Harrell both wanted to see Chevy reclaim top honors on the drag strip. Together they hatched a plan to enable this, by shoehorning a big-block into the lightweight and compact Camaro.

Gibb contacted Vince Piggins, head of product performance for Chevrolet engineering, late in the summer of 1968. Piggins, the person within the Chevy corporate structure who approved of COPO production, loved the idea Gibbs pitched him. To get such a drag car made though, would require at least 50 street-going versions be ordered by an authorized Chevrolet dealer.

The clean, unadorned lines of a Cortez Silver COPO ZL1. (Photo courtesy of Hemmings News.)

To satisfy this, Gibbs placed an order for the street examples, and Piggins duly approved of what became COPO package 9560, thus setting the stage for one of the most legendary Chevrolets ever produced.

The car that Gibb and Harrell envisioned had, at its heart, a beast of an engine – the Chevrolet ZL1.

The heart of the COPO Camaro – the mighty ZL1 engine. (Photo courtesy of Hemmings News.)

Based on the famous Chevrolet racing L88 motor which in Corvette form had an iron block and heads, the ZL1 featured a cast-iron sleeved aluminum 427 block with wet-sump lubrication and accommodation for a mechanical fuel pump. It ran with forged-steel internals including a solid-lifter camshaft with .560-inch lift intake/.600 exhaust, 359 degrees duration, and a 12.5:1 compression ratio underneath aluminum open-chamber cylinder heads. Resting on top was a single 850-cfm Holley double-pumper.

Along with a K66 transistorized ignition system, the ZL1’s goodies boosted output well past the factory 430 horsepower rating it shared with the L88. In truth, it churned out in excess of 500 ponies, making it the most powerful engine Chevy had ever offered to the public. What’s more, it was a lightweight powerhouse, with the extensive use of aluminum limiting the engine’s weight to just 500 pounds.

The aggressive front end design. (Photo courtesy of Hemmings News.)

Interestingly, the COPO cars began life as SS Camaros equipped with the 396 V8. Following an “Exception Control Letter Sheet” that stipulated the components to add or remove from a COPO vehicle, the 396 was deleted on the assembly line and replaced by the ZL1 engine.

A choice of the M20 wide-ratio or M21 close-ratio Muncie four-speed manual or the M40 three-speed Turbo-Hydramatic was offered depending on the buyer’s preference, and a 4.10:1 differential with heat-treated ring and pinion and Posi-traction limited-slip sat in the back.

Added to the car was the F41 heavy-duty suspension including heavy-duty springs with five-leaf rears, a heavy-duty radiator, power front disc brakes, F70x14 white letter tires, and a steel cowl-induction hood.

The spartan interior. Note the three-speed column shifter. (Photo courtesy of Hemmings News.)

All of the cars came with a black vinyl, no-frills interior with a radio delete. Exterior trim was limited to Bow Tie emblems on the grille and rear panel, and Camaro badges on the fenders and deck lid.

A COPO ZL1 in Fathom Green. (Photo courtesy of Haggerty.)

Only five exterior colors were available, including Cortez Silver, Dusk Blue, Fathom Green, LeMans Blue, and Hugger Orange.

The car carried a full 5-year/50,000-mile warranty and was fully street-legal.

A COPO ZL1 in Hugger Orange. (Photo courtesy of ClassicCars.com.)

The performance of the COPO ZL1 was staggering for the day. With the stock dual exhaust and tires, the car could trip the quarter in the low 13s. A little tuning, custom exhaust headers, and slicks would get the COPO ZL1 into the mid 11s at roughly 120 mph.

But the cost of achieving those times in the late 1960s was not cheap. The ZL1 engine alone added $4,160, pushing the sticker price of the COPO Camaro to a then astronomical $7,269. Owing to this, Gibb had trouble selling the cars, taking until 1972 to do so, and other dealers only ordered 19 more over the original fifty examples.

The no-frills rear end of the COPO ZL1. (Photo courtesy of Barrett-Jackson.)

As such, the 1969 Camaro COPO ZL1 was an exceedingly rare car, to begin with, and more than half of them were raced hard and trashed. Because of that, restored, factory numbers-matching COPO ZL1s have sold in recent years for in excess of $1 million.

A huge price to pay by anyone’s standard, but to some, worth it for the privilege of owning one of the world’s greatest Rare Rides.