Charles Kettering, one time head of research at General Motors, once said: “People are very open-minded about new things – so long as they are exactly like the old ones.” Studebaker tried to prove him wrong but lacked the capacity to make an impression. Then came the Mustang. Ford’s Pony Car was definitely a “new thing” for America’s automotive market.

A Brief History of Ford

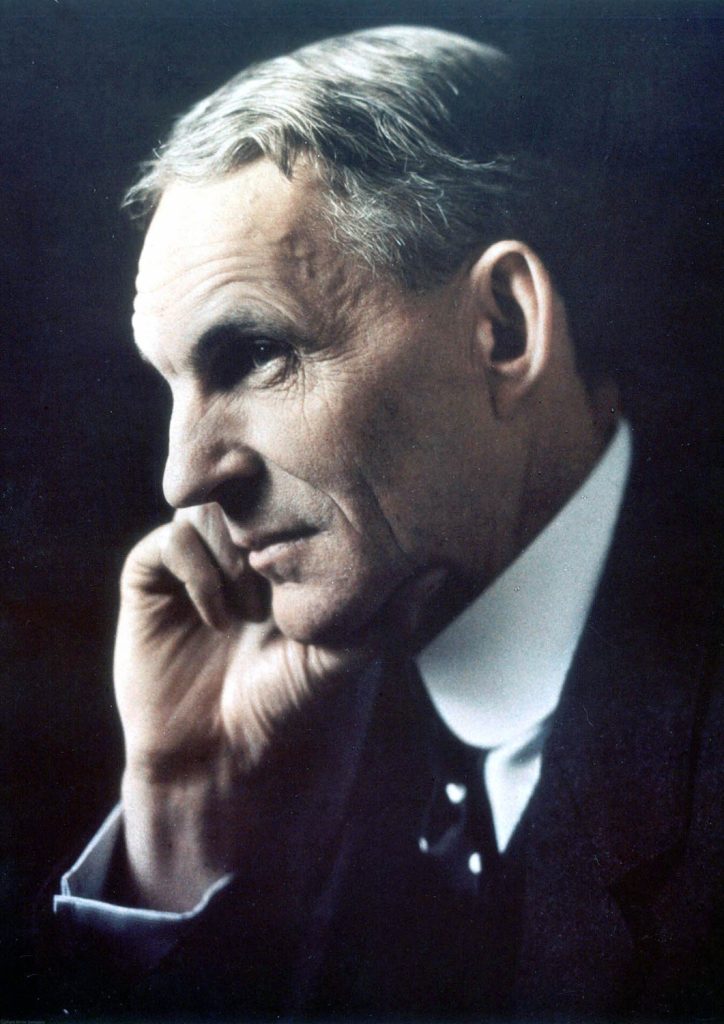

Any story about the Ford Motor Company has to start with Henry. He was the son of an Irish immigrant who fled the Irish Potato Famine in 1847. Some stories about Henry claim he was a poor kid who made good. In fact, by the time Henry was born in 1863, his father owned several hundred acres of farmland near Dearborn, Michigan, and was a fairly successful farmer. Henry, though, became fascinated with a steam traction engine and showed little interest in farming. In the “Beaulieu Encyclopedia of the Automobile,” Henry’s father is quoted as saying that he was “a lad with wheels in his head.”

His interest in technology eventually resulted in his becoming Chief Engineer for Edison Illuminating Company after become friends with Thomas Alva Edison. But, he still had “wheels in his head,” which led him, in 1896, to build his first automobile in a workshop at his home in Detroit. He had only one problem once the car was finished – the door to the workshop was too narrow to allow the car to get out. Henry did the only logical thing, he demolished the doorframe, including removing bricks around the frame. Once outside, Henry’s experiment showed its speed, reaching 20 mph. He was able to sell the car for $200, which financed his second car in 1898. This one was more sophisticated than his first automobile, and it attracted the attention of people with money to invest in a new business. The Detroit Automobile Company was born, thanks to those backers. However, it was short lived. Only one vehicle was built, and it was not successful. The company closed in January 1901.

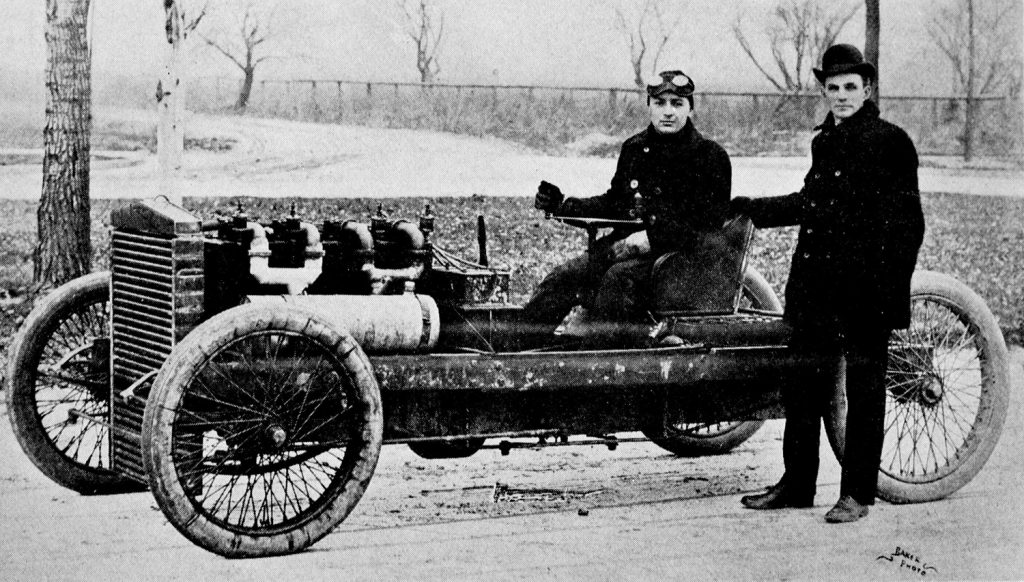

Henry’s next step was to build racecars in order to attract attention to his abilities. He built one called “Arrow,” but it was his “999” that attracted the most attention. 999 was a 18.9-liter, four-cylinder racer producing 80 hp. 999 set records, including a flying mile of 91.37 mph. Barney Oldfield drove 999 to a win in the Manufacturer’s Challenge Cup in 1902, covering the five miles in 5 minutes 28 seconds. These successes were enough to attract the attention and financing of Alexander Young Malcolmson, who Henry knew from his days at Edison Illuminating Company. Malcolmson’s company supplied coal to Edison. Together, they formed Ford and Malcolmson in 1902. The company was reorganized as Ford Motor Company on June 16, 1903.

Henry chose an alphabetical approach to naming his products. The first was, logically, the Model A. It had a 1645-cc, two-cylinder engine mounted under the seat. It used a two-speed epicyclic transmission and chain drive. The two-seater sold for $850, or over $100 more than a Cadillac. The first car was sold in July 1903 to Dr. E. Pfennig, a Chicago dentist. “Pfennig” is a German word that translates as “penny.” The good doctor spent a lot of pennies to buy the first Ford automobile.

Sales of the Model A were good, despite its cost, and the company was in good shape. Still, it was primarily an assembly plant. Engines and running gear were produced for Ford by the Dodge Brothers. Bodies came from the C.R. Wilson Carriage Company. Hartford Rubber Company provided tires, and wheels came from the Prudden Company.

There were new models announced in October 1904. The Model AC had a larger engine, and the Model C had that larger engine and new bodywork. The Model B caused some friction in the company. Promoted by Malcolmson, it used a 4646-cc, 24-hp, front-mounted, vertical four-cylinder with shaft drive. Its price was $2000, and Henry was not pleased. The authors of articles in “The Beaulieu Encyclopedia of the Automobile” reported that “Henry was determined that cars should cater for as wide a section of the populace as possible, and so they had to be inexpensive and made in large numbers.” Differences in the company philosophy resulted in Henry maneuvering Malcolmson out of Ford in 1906, leaving Henry to make cars that fit his marketing beliefs.

Ford became a serious manufacturer with the opening of the Piquette Avenue plant in 1904. By the summer of 1906, production was up to 100 cars per day. Production included the Model F, a derivation of the Model C; Model N, a front-engined four-cylinder producing 18 bhp from 2442-cc and selling for $500; and Malcolmson’s final project, the Model K, with a 6636-cc, six-cylinder that cost $2500. After Malcolmson’s departure, Henry ended production of the Model K and would not have another six-cylinder engined Ford until 1941.

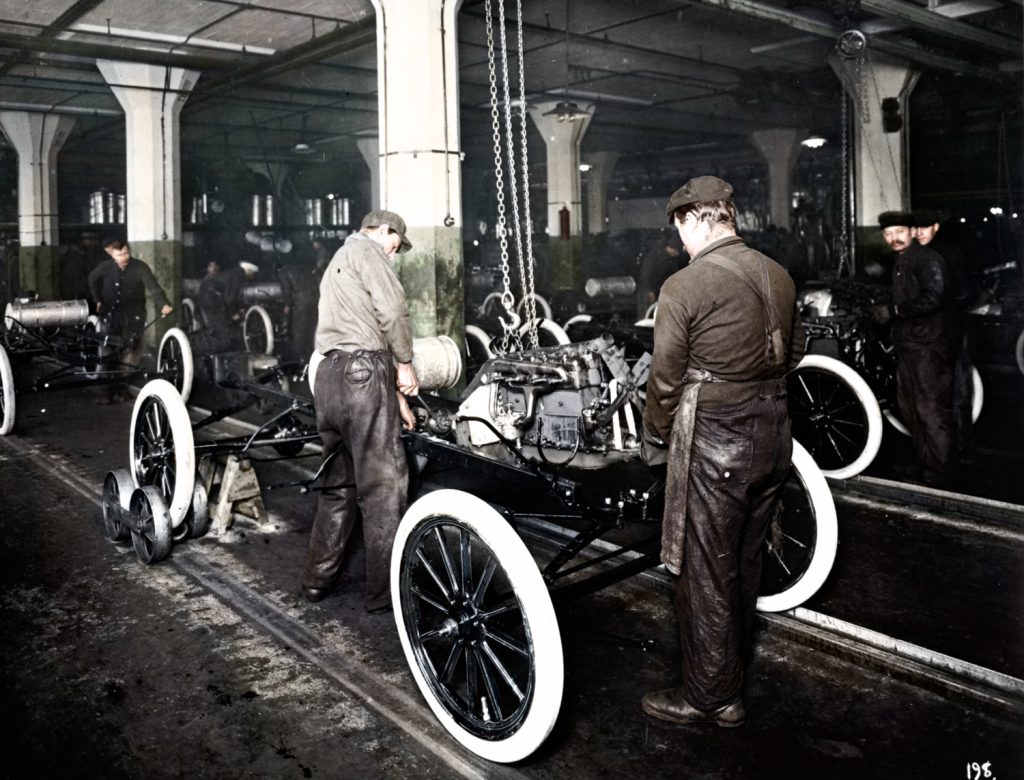

Then came the Model T, and Ford became a powerhouse among American auto manufacturers. Eventually, some 15,000,000 of the 2896-cc, four-cylinder cars would be built. In 1911, Ford was making a $50 profit on every car, and as production increased the price of the car came down, further increasing sales. The first year of mass production at the Highland Park plant, in 1914, saw 308,162 Model Ts leave the plant. The number two years later was 734,811.

Ford enthusiasts can thank Henry’s son, Edsel, for the first big change at Ford. Henry made Edsel president of the company in 1918, although Henry still made the big decisions. Edsel was able to convince his father that the time of the Model T was over, and the new Model A became the focus of the company on May 25, 1927.

The Ford Motor Company maintained its place among American auto manufacturers throughout the Depression. During WWII, the company was a significant manufacturer of military equipment. There were also some changes at the top. Edsel died in 1942, putting Henry back as the official president of the company. At Henry’s age, though, he felt it prudent to step down for good. In 1945, Henry’s grandson, Henry II, aka “HF2 or Hank the Deuce,” became the president of Ford. Henry died two years later.

Henry II took over a company in the red. He brought in new people, reorganized Ford, and stopped the losses. One of the new people who eventually joined the company was Lido Anthony Iacocca, known as Lee. Iacocca’s route to the upper floors of Ford was a bit unusual. Deemed 4F, Iacocca was unable to enlist during WWII, so he remained in school. He received a B.S. in engineering from Lehigh University and a Masters of Mechanical Engineering from Princeton. He first joined Ford as a trainee engineer, where he learned he didn’t care for production engineering. Iacocca wanted to be in marketing and sales, so he left headquarters and went to work for a Ford dealer in Chester, Pennsylvania. He rose steadily in the Ford system and was noticed by Robert McNamara, then Ford’s President, when sales in the Philadelphia district he oversaw soared. McNamara made Iacocca manager of truck marketing. Iacocca was soon promoted to be the head of car marketing and, in November 1960, he became the Vice President/General Manager of the Ford Division. Early in his career with Ford, Iacocca said he wanted to be a vice president by the time he was 35. He made it one month before his 36th birthday.

Design at Ford had been conservative under McNamara. He believed that all models should be designed to make money – costs were to be kept down. When McNamara left to be President John Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense, the Ford Motor Company began a period of innovation and excitement. Iacocca was very much a part of that. He influenced the 1963 model line-up and was responsible for putting a V8 engine in the Falcon, creating the Sprint. The Sprint, and Chevrolet’s Corvair Monza, became popular with younger buyers, and Iacocca noticed and believed it was time for Ford to create a car with a particular appeal to the youth market. Ford’s Public Relations Department had been receiving letters asking that Ford recreate its early Thunderbirds – the two-seaters from 1955-1957. The interest in having a sportier car was also validated by public opinion research. Baby Boomers were the right age for a sporty car. The number of people between 15 and 29 years of age was increasing dramatically, and they were better educated and more affluent than their parents. Of the people under 25 who were polled, 36% wanted bucket seats and a four-speed transmission.

Mustang

With the support of the PR Department, Iacocca undertook to produce a youth-oriented car that would satisfy the apparent demand. He approached Ford senior management and received Henry Ford II’s support; the project was approved.

There would be three Mustang prototypes introduced between 1962 and 1964. The first, “Mustang I,” was primarily the result of the design efforts of John Najjar, Executive Stylist, Exterior. As the design developed, the stylists began calling it “Mustang,” because it reminded them of the P-51 Mustang fighter plane of WWII. Najjar received permission to develop a prototype, and he began work on the exterior. Roy Lunn, formerly with Aston Martin, was tasked with engineering the car. The Mustang I was targeted at small British sports cars, like the MG and Triumph. The prototype was a small, mid-engined car, weighing 1148 pounds, and standing only 40 inches high. It was very aerodynamic, including having retractable headlights. The engine, a 60° V4 developed by Ford’s German operation, had a displacement of 1497-cc with overhead valves and twin Weber carburetors producing 109 bhp at 6400 rpm. A single Solex version was intended for the street and produced 89 bhp. Both had a four-speed transmission. Construction of the prototype was outsourced by Ford to Troutman & Barnes, who worked 24/7 to get it ready for its introduction.

The Mustang I was introduced to the public at the United States Grand Prix at Watkins Glen, NY, in October 1962. Dan Gurney and Stirling Moss both drove the Mustang I on the Grand Prix course and liked it. Car & Driver tested the car and said it was better than a Cooper-Climax sports racer they had recently tested, although they criticized it for a lack of storage. British magazine, Autocar, also tested the prototype and called it “delightfully light yet precise.” Iacocca killed it. He said it had no potential to reach a large market. The “Encyclopedia of American Cars Since 1930” quotes Iacocca as saying, “That’s sure not the car we want to build, because it can’t be a volume car. It’s too far out.”

The goal was to have the production Mustang ready for the World’s Fair in New York City in April 1964, so progress needed to be accelerated. Iacocca formed the Fairlane Committee—so named because they met at the Fairlane Inn—to develop the design guidance for the production model. The committee decided that the car would be “youthful and sporty,” have four bucket seats, Falcon driveline, weigh about 2500 pounds, be less than 180 inches in length, have a standard transmission, and cost less than $2500. It would also have a long list of options.

Iacocca tasked four styling teams to come up with a clay model within three weeks. Dave Ash, assistant to Ford Styling Chief, Joe Oros, developed the design that was selected to be presented to the Ford executives. It was initially called “Cougar,” but that name was changed to “Torino” before settling on “Mustang II.” Henry II liked it, and Project T5 was underway for production engineering on September 10, 1962. The prototype Mustang II was shown before the US Grand Prix at Watkins Glen in October 1963 as the final production model was being finalized.

But what to call the car? Suggestions included Allegro, Cougar, Torino, and Mustang. Henry II suggested Thunderbird II or T-Bird II. Iacocca liked animal names, and he talked with John Conley who was with J. Walter Thompson, Ford’s ad agency. Conley produced a list: Bronco, Puma, Cheetah, Colt, Mustang, and Cougar. Finally, the name that had stuck with the prototypes won – the new car would be the Mustang because of the image it produced of wide open spaces and cowboys.

The target market for the Mustang was the 16-24 age bracket. It was the only thing Iacocca and his team got wrong. Prior to the launch, a market survey was done with 52 couples, all car owners, and from a variety of income levels. When they saw the car, they all liked it and estimated the cost to be well over $2500. When they learned the price, they all wanted to buy one. As the launch date, April 17, 1964, approached, the Mustang became one of the worst kept secrets in the automobile world. Ford bought 9:00pm slots on all three networks on April 16th, and 2600 newspapers had ads for the Mustang on April 17th.

After its debut, Ford worked hard to spread the word about the Mustang. A variety of college newspaper editors were given Mustangs to drive for several weeks. Journalists were given Mustangs to drive the 700 miles from New York to Dearborn. Prior to the launch, 8160 Mustangs were built to insure that every Ford dealer in the country had at least one on the showroom floor. Over 4 million people visited a Ford dealership the first weekend after the car’s debut. 100,000 Mustangs were sold in the first four months. Iacocca switched the San Jose, California, plant to producing Mustangs as a result of the incredible demand for the car. Time magazine called the Mustang “a Ferrari for the masses.”

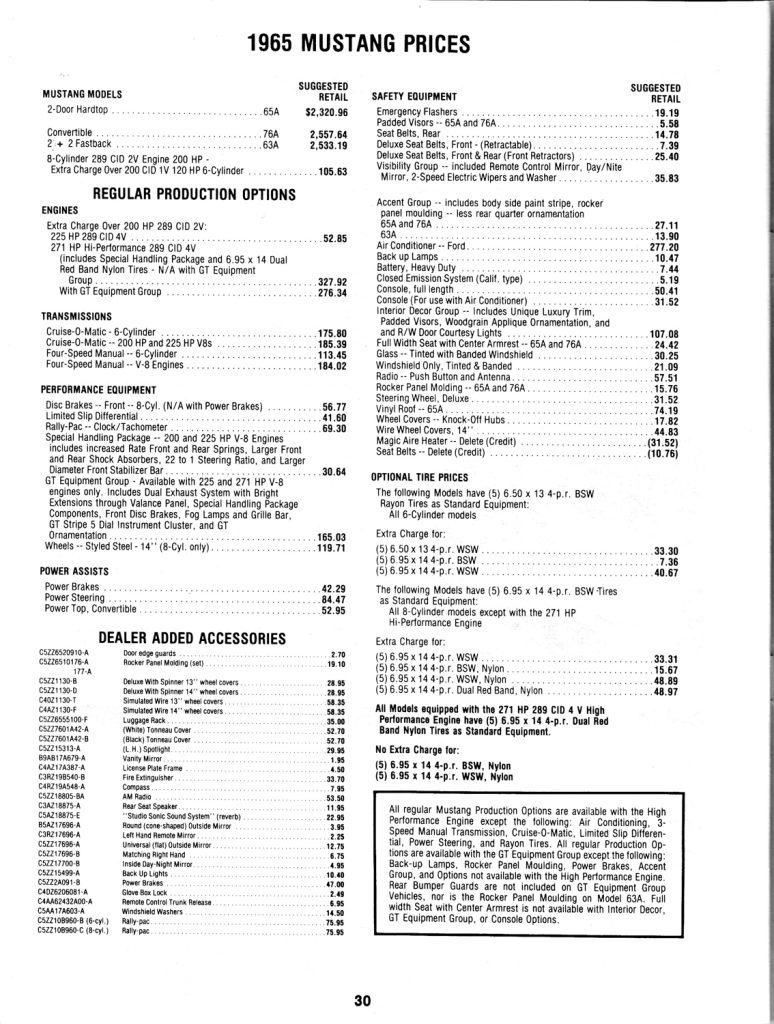

All this happened because Iacocca believed in a different kind of car – what has become known as a “pony car.” It was attractive and well proportioned, and it had little unnecessary glitter. Iacocca gave the Mustang buyer a choice of two body styles, five engines, six transmissions, three suspension packages, three brake systems, and three wheel sizes, in addition to a variety of other performance and comfort options. The appeal was well beyond the 16-24 age group – everyone liked it. First year sales set a record for a new model – between April 1964 and September 1965, a total of 680,989 Mustangs were sold. No wonder it sold well, buyers could choose to have an economy car, sports car, luxury car, or a drag racer. The most popular Mustang was the hardtop; the least popular was the bench seat convertible.

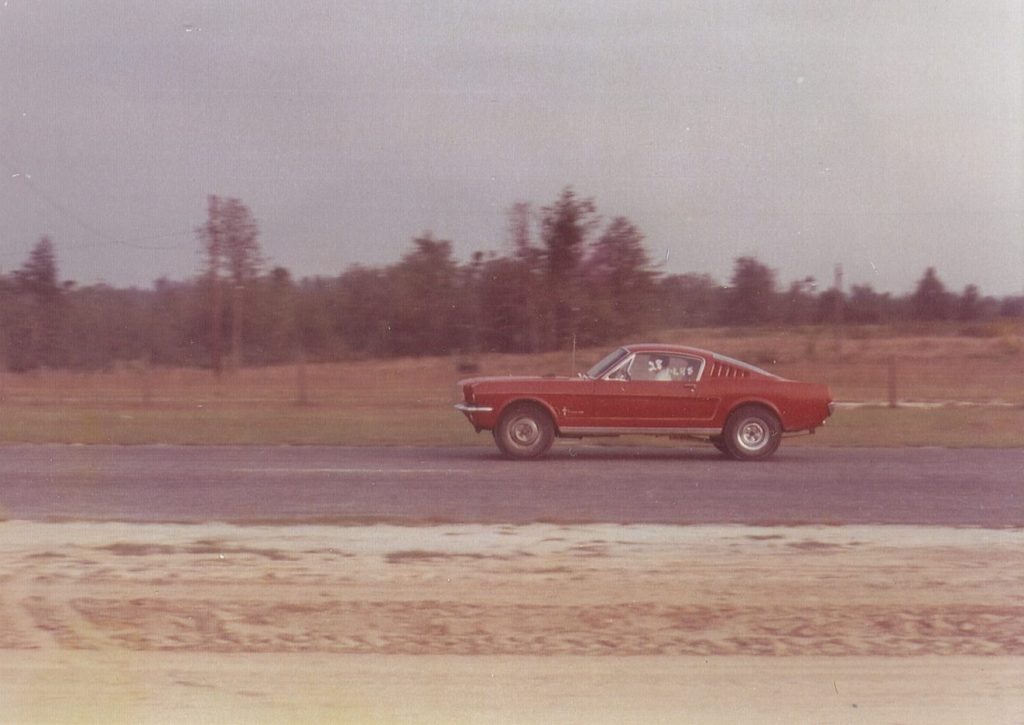

In September 1964, Ford added a third body style, a fastback 2+2. There were two engine changes for the fastback – the 260 cu.in. V8 was dropped in favor of a 289, and the 170 cu.in. 6-cylinder was replaced by one of 200 cu.in. In “Mustang Rides the Market,” published in Automobile Quarterly Volume III, Number 3, L. Scott Bailey praised the fastback: “Using options, it closely approaches the definitive meaning of a G.T. . . . While the rear passenger bench can hold two in modified comfort, the Mustang Fastback is at its best when the seat is in its folded state, allowing room for skis and luggage in the proper luxury of a two place GT.”

VIN 5R09K1250001

A few lucky people have found significant cars. Some put the car away, not allowing anyone to see their icon. A larger group show their car with signs saying “Look But Don’t Touch.” Another group shares their cars completely – they show the car, allow people to get in it and experience what it is like to sit behind the wheel of the car, and, sometimes, allow people the full experience of driving the car. Lawrence and Tees Booth are in that last group. They are Mustang enthusiasts. Tees first Mustang was a 1967 3-speed that she reluctantly sold after college. Lawrence still has the 1968 ½ Cobra Jet Fastback that was his first Mustang at age 17. As Lawrence says, “Over the years, Mustangs have come and gone,” but they’ve added a number of significant Mustangs to their collection – 1968 ½ Coupe, ’68 Shelby GT 500 KR convertible, ’69 Shelby GT 500 convertible, ’70 Boss 429, ’14 Shelby GT 500 convertible, and ’15 50th Anniversary Mustang (#1373). But, none of these are as cool as their 1965 Mustang Hi-Po Fastback, with the serial number ending in 001.

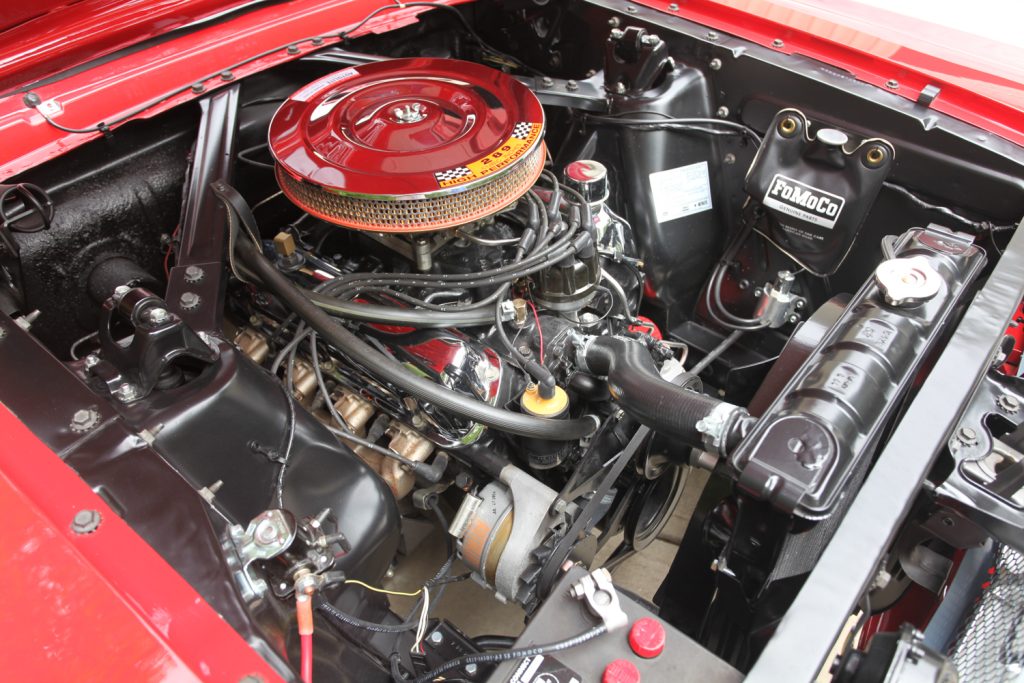

The Booth’s red 1965 Fastback is the first Fastback to come off the assembly line at the Ford San Jose plant in 1964 – August 20, 1964. It is such an early car that it shares parts with the original 1964 ½ Mustangs, including the hood, headlight buckets, and some wiring. Theirs is a truly “numbers matching” car. All the sheet metal panels, engine, drivetrain, carburetor, transmission, distributor, etc. are either stamped with the original VIN or have the appropriate date code for the car.

Lawrence did quite a bit of research on the car. It was originally sold in the Denver region to a member of the military. He took it first to Virginia then to South Carolina. That owner traded the car at a Chrysler dealership in Batesburg, SC. Simon Buzhardt bought it from the dealership, owned it for a year and traded it in on a new Road Runner. George Hichenbottom bought the Mustang from the dealership, owned it for about a year, and, like Buzhardt, traded it back to the Chrysler dealer. It was then bought by Jeff Taylor in December 1969, while on leave from the Army. He took the car to the drag races, where he raced against Buzhardt in his Road Runner and beat him with the very Mustang he once owned.

None of these owners understood the significance of this Mustang. Taylor parked it in 1973 to rebuild the engine and never completed the rebuild. Thankfully, the car was in dry storage. It had traveled about 58,000 miles on the road and spent time on the drag strip. The car remained complete and original, with no rust and no body damage.

J.R. Shelby, a friend of the Booths, knew of the car and finally convinced Taylor to sell it in 2008. When he got it home and started cleaning it, he saw the VIN, researched the car, and realized that he had an important Mustang. The Booths were lucky they knew Shelby, who liked to “restomod” his cars. Shelby didn’t want to sell the car to Lawrence, but, Lawrence, knowing that he was going to make changes and updates, convinced him to take lots of photos of the car in its original state and save all the original parts, including fasteners, in a five gallon bucket. When Lawrence was finally able to convince him to sell the car, Lawrence got all those discarded parts and was able to put the Mustang back to original. He got to spend many hours searching for the parts he needed and sorting and cleaning them.

Tees Booth wrote about the car in an article titled, “What do you do with a historically significant 1965 Mustang Fastback 2+2? Share it!!!!” She tells that story well:

“From the time Lawrence brought this special Mustang home in November of 2010, the love affair with this special car began. Every Mustang is ‘special’ to its owner, but what makes a Mustang historically significant? This special Mustang is the first 1965 Mustang, first fastback and first K-code Mustang to receive a VIN from the Ford San Jose Plant in August 1964. VIN 5R09K125001. When the car arrived, the previous owner had completed a frame-off restoration, but had chosen to make some modifications to the stock Mustang. Our goal was to return this special Mustang to its original Ford showroom condition. This quest began in earnest and continued through the 50th Anniversary in Charlotte where we were asked to display our car at the collection of 50 Rare Mustangs. As the restoration continued, we began entering the 1965 Mustang Fastback in MCA [Mustang Club of America] events so that the 1965 Hi-Po experienced enthusiasts could judge and make recommendations to continue work on the restoration. The 1965 Mustang was shown in the CTA Class, (Concours Trailered), which gave the car a different level of scrutiny. Due to the judging rules for MCA, no reference to the historical significance of the 1965 Mustang could be displayed, however the Georgia license tag reads: 1 ST 65 FB. Several judges knew the historical significance of the Mustang and our goal to return it to stock condition. They were most helpful in providing information and insight. It was fun to meet Mustang enthusiasts at the National MCA events and find out that we would have to explain some items on this very early Mustang. Yes, it was built so early in the 1965 Mustang model year, that it was built with a 1964 ½ hood and headlight buckets. Some of the wiring from 1964 was also used on the car. Does a restoration every end? After almost ten years of ownership and numerous MCA and other awards – if these cars are driven – even occasionally, there is always something that will need maintenance. “

The Booths have shown the Mustang at numerous shows and concours, winning a number of awards along the way. I met them originally at the first Atlanta Concours d’Elegance, but we lost touch. I met them again at the Highlands Motoring Festival in 2019. Tees picks up the story:

“A recent Motoring Festival that we attended with the Mustang was in Highlands, NC. The weather and rain were questionable, however it was just sprinkling rain on Saturday morning, so we took the car out of the dry enclosed trailer and into the rain. Many people had come from long distances to see the Festival cars and support the various charities. This event was planned at least a year in advance and so off we went – windshield wipers going and head lights on. The car sat in the pouring rain for a number of hours while the judges and people with umbrellas and rain gear couldn’t seem to get enough of the Rangoon red 1965 Fastback and the Hi-Po engine. We were asked to move the car, and then were told that our car had won Best of Class – American Performance – and Best of Show. It was quite an honor since our 1965 Mustang Fastback was only one of many very significant cars attending the event. We left wondering if the car would ever be dry again, but delighting in the fact that the little 1965 Mustang Fastback had been awarded such accolades. We were thanked immensely by the organizers for bringing our car out in the rain and participating in the event. Actually, we had a great time sharing the ‘car weekend’ with friends who were attending the event with their cars as well.”

Tees added a comment about sharing: “When we were at the Hilton Head Concours d’Elegance, Keith Martin of Sports Car Market magazine, suggested that if car owners would do more to share their cars with the younger generation, these young folks would become enthusiastic about the classics as well. Once our car is judged, we have great fun letting the ‘younger generation’ sit in the car and make pictures. It’s as much fun for us as it is for these young adults getting to sit in the car.”

Driving Impressions

I like early Mustang Fastbacks. I think they are the best American automobile design ever. Of course, I’m a bit biased, since my first new car was a ’66 Fastback – GT 350. So, climbing into the Booth’s ’65 was like being home. You just don’t forget your first car. So much was the same – seats, gauges, pedals, controls, shifter. But, there were differences. The tach in a GT 350 was dashtop mounted. There was a tach and clock mounted on the steering column. I remember a different steering wheel in the Shelby – wood rimmed, maybe? Seat belts in the Shelby were “competition” belts, so they had the aircraft type latches instead of the standard ones. Badging, of course, was different. All in all, very familiar. The gauges include a fuel gauge on the left, then speedometer and temperature gauge. Heater controls are in the middle. Knobs and emergency brake all standard, as well as the oil and alternator idiot lights. The shifter for the four-speed transmission has a T-bar for engaging reverse – pull up on the T-bar, then move the shifter to the left and back, next to second gear.

Starting is simple – turn the key, and it starts. Into first gear and release the clutch, and we’re off. It’s a pretty steep hill from Lawrence’s shop past the house and to the street, and the car pulled nicely. Onto the roadway, and acceleration is quick and steering precise. Lawrence is fine with opening the car up a bit – “Does it good to drive it,” so off we went down a four-lane suburban road. Nice – makes me smile to remember driving my Mustang the same way. A U-turn to head back reminds me how tight the turning circle of a rear-wheel drive car is. The car shifts smoothly, accelerates well, brakes like it should, turns precisely, and just feels good to drive. Lawrence adds that he restores a car to “perform like it did on day one.” He’s left nothing on this car untouched, and it is a truly nice car in every way. After parking the car, I kept looking back at it as we walked to the house and wondered if I could add garage space to my house so I could own an early Mustang Fastback – I’m in lust again.

Bailey wrote in his 1964 Automobile Quarterly article “The Mustang is a car of many personalities. It represents a significant attempt to capture some of the many individual desires of an increasingly informed and car-conscious America. Only time will tell if the Ford Mustang multi-car concept really means all things to all drivers.” Well, it’s now 2020, 56 years since he wrote that article, and the Mustang is still a solid seller. Apparently it still “means all things to all drivers,” or at least to most of us.

Lawrence and Tees Booth have been incredibly gracious and immensely helpful with this article. They are wonderful people, and #1, as they call the Mustang, is in good hands.

Specifications

| Body Type | Unibody 2+2 fixed head fastback coupé |

| Wheelbase | 2743 mm/108 inches |

| Track, front and rear | 1422 mm/56 inches |

| Length | 4613 mm/181.6 inches |

| Width | 1732 mm/68.2 inches |

| Height | 1300 mm/51.2 inches |

| Curb Weight | 1188.9 kg/2621 pounds |

| Engine | 90° V8 OHV with two valves per cylinder |

| Displacement | 4747 cc/289 cid |

| Bore/Stroke | 101.6 mm (4 inches)/72.9 mm (2.87 inches) |

| Horsepower | 168 kW/225 bhp at 4800 rpm |

| Torque | 414 Nm/305 ft-lbs at 3200 rpm |

| Compression ratio | 10:1 |

| Induction | Single 4bbl carburetor |

| Transmission | 4-spd manual |

| Drive | Rear-wheel drive |

| Front suspension | Independent with coil over shocks |

| Rear suspension | Solid rear axle |

| Brakes | Drum front and rear |

| Wheels | 14 inch |

| Tires | 6.95×14 |