For many enthusiasts, the muscle car hobby is a means of returning to something once lost. Memories of rumbling V-8s, fat tires, loud pipes, and lots of burned rubber linger fondly in the minds of gearheads, leaving a desire to return to those halcyon days of horsepower and speed.

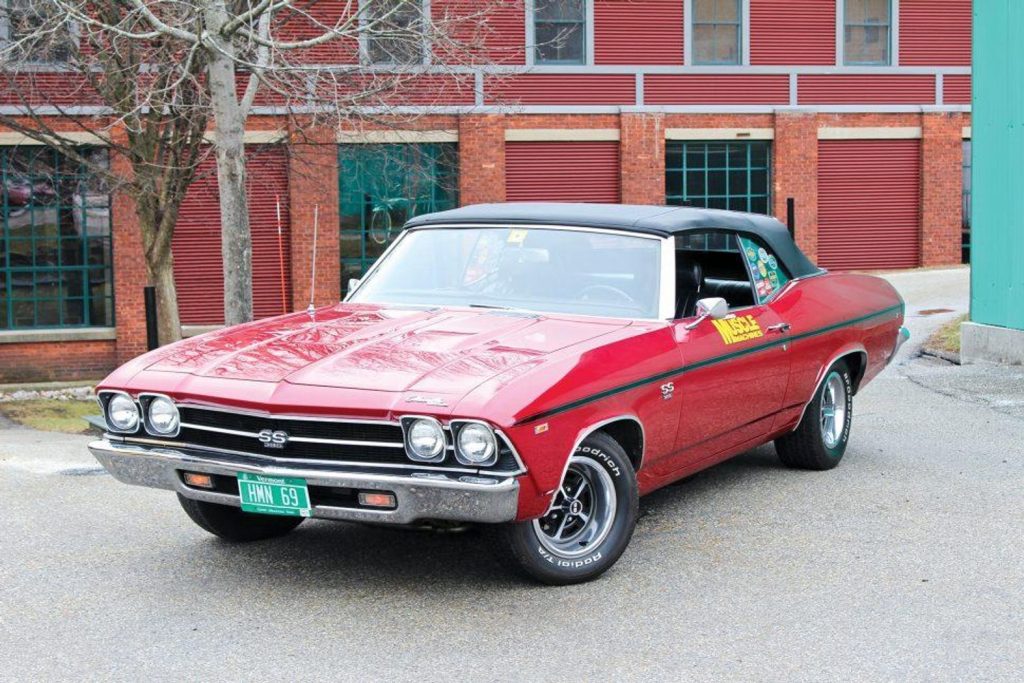

Hemmings Motor News has owned this 1969 Chevelle SS 396 convertible for 20 years or more, maintaining it in stock form and preserving the late-’80s restoration it received prior to joining the company’s collection. It has the 396/350-hp engine and a TH-400 automatic, with a set of 3.31 gears in a factory 12-bolt Posi rear. It ran and drove fairly well in this configuration, but the drivetrain wasn’t as rowdy as you’d hope for from a big-block Chevelle.

The thing is, when the long-awaited day finally arrives for that first drive, a disparity between memory and reality may be felt, as the experience turns out to seem less glorious than anticipated. We can blame some of this on human nature and our tendency to steadily make more of the good ol’ days than there ever really was, but that doesn’t account for all of it.

The somewhat tepid street performance of our Chevelle left us wanting more, and the best place to start seemed to be a baseline ¼-mile test. We weren’t expecting much from the initial passes, which featured zero car prep, aged Radial T/A tires, and a messed-up shift cable that prevented any manual shifting of the TH-400. In spite of all that, we still managed a series of mid-15-second passes at Lebanon Valley Dragway— better than we were expecting.

A large part of our disappointment probably has more to do with our standards for performance, which have been slowly rising since about the mid-’80s. By the time the new millennium dawned, the average car buyer had become intolerant of anything that couldn’t get up and go with some degree of alacrity. That’s how we ended up with 14-second Honda Accord sedans. Meanwhile, even entry-level six-cylinder Camaros and Mustangs can now run 13-second quarter-mile times; the lowest-level V-8 versions are mostly 12-second rides.

For the benefit of the video cameras that were rolling for this pass, we made some smoke, but in reality, big burnouts usually don’t help traction with regular street radials. With some tuning and a shifter that would have allowed us to hold out longer for the 2-3 shift, we might have gotten into the 15-ohs, but that’s still not too impressive these days. We wanted more.

Sure, there are lots of ’60s and ’70s muscle cars that can still tear your face off, but most of those aren’t really stock. At a minimum, they have camshafts, intake manifolds, and exhaust systems that all benefit from years of research and refinement. Beyond the bolt-on bits, stroker crank kits and high-flow aluminum heads have become far less exotic, and are options frequently exercised by enthusiasts when rebuilding muscle-era engines.

Back in the day, not every muscle car had the snot of a 4.10-geared Six-Pack Super Bee or an LS-6 Chevelle. A ’69 GTO with a standard 350-hp 400 and an automatic is a fine car, but if it’s just as Pontiac left it, you may not feel quite the thrill you anticipate behind the wheel after all this time.

While we could have started swapping parts on the 396 to increase its output, we really didn’t want to mess around by altering what is possibly this car’s original engine (the numbers appear to have been machined off the deck during a rebuild). Instead, it seemed like a better plan might be to build a bigger big-block for more power, while leaving the stocker in storage for now.

Was it all for naught, then? Were we pining for something that never was? Should we all just give up and apply for a mortgage to finance a Hellcat? Of course not. The style and simplicity of vintage muscle is something all its own, and too good to forget. We just have to figure out how to stoke the fire a bit.

OUR OWN TIME MACHINE

Much of this talk about disappointed driving has come to us through our interactions with our readers and other muscle fans out in the world, and the theme has been raised enough times that we knew it was more than just anecdotal. But it really hit home when we got out the Chevelle that Hemmings has owned for many years as part of the company car collection, housed in our “Sibley Shop” garage and museum adjacent to our offices.

We started to look into building a 454 when we came across the listing for the Chevrolet Performance (formerly GM Performance Parts) ZZ427. This is a brand-new engine based on a 454 block but using a crankshaft that yields that magical 427 cubic inches, which just seems right for a ’69 Chevelle. This crate engine is rated a 480 hp using a hydraulic roller camshaft and aluminum cylinder heads. It comes complete, even including a Holley 4150-style vacuum secondary carb and an HEI-style distributor from MSD. There’s even an aluminum water pump and ATI Super Damper crank balancer.

The ’69 SS 396 convertible is a great example of the breed, in stock condition with a hydraulic-cammed big-block, a TH- 400, and a 12-bolt with 3.31 gears and a Posi. It’s got buckets and console shift, power steering and power disc brakes, and a power top. There is no air conditioning, power windows, tilt column, or any further frippery. It’s a modestly optioned car that has survived the years in good stead, having been treated to some form of restoration in the late ’80s that was probably more in line with what we’d call a refurbishment today: new paint, rebuilt engine, freshened suspension. We don’t believe this car has ever been completely dismantled.

Once the new engine arrived, we began the swap process by removing the stock engine and transmission. Big-blocks are heavy, especially when they still have iron heads, intake manifolds, and exhaust manifolds, like this 396. We opted to pull the transmission separately before yanking the engine.

A while ago in HMM, I wrote an editorial about driving this Chevelle after taking it down to one of our Musclepalooza events. It was a trip on two-lane secondary roads that normally takes about an hour, but the familiarity of driving a Chevelle sparked nostalgic sensations that kicked in before I’d gotten off my street.

The stock TH-400 was greasy but sound, and it had the kind of firm engagement we recall from other Chevy big-block automatics we’d lived with years ago. It does appear to be this car’s original unit, so we’ll store it for a future resto. In the meantime, we removed the driveshaft, shifter cable, speedometer cable, and kickdown switch connector, unbolted the torque converter, the rear mount, and the crossmember, and then pulled the bellhousing bolts and lowered it slightly to get the cooler lines off.

But, after the warm, fuzzy sensations of nostalgia cooled, it became increasingly apparent that the 396 wasn’t going to put a stupid grin back on my face. It churned out lots of low-end grunt, but it didn’t have much snap.

After disconnecting the exhaust system from underneath, we lowered the car and drained the coolant before pulling the fan, shroud, and radiator. Then we removed the engine-mount bolts and disconnected the underhood wiring and hoses, and unbolted the power-steering pump and tied it off to the side. The engine was then free to come out.

Looking at the specs, it’s no wonder. The standard 396, rated at 325 hp, was essentially an optional upgrade for fullsize Chevys—a high-torque engine to help provide more “passing power” for Impalas and Caprices. The cam specs look like they were selected for a luxury car, where a smooth idle and strong “launch feel” were the goals. Stepping up to the 350-hp version brought a hotter cam, more in line with a performance engine— this is what our car is supposed to have. The 375-hp version was, of course, another animal altogether, with square-port heads, more compression, an aggressive solid-lifter camshaft, and a big Holley carb.

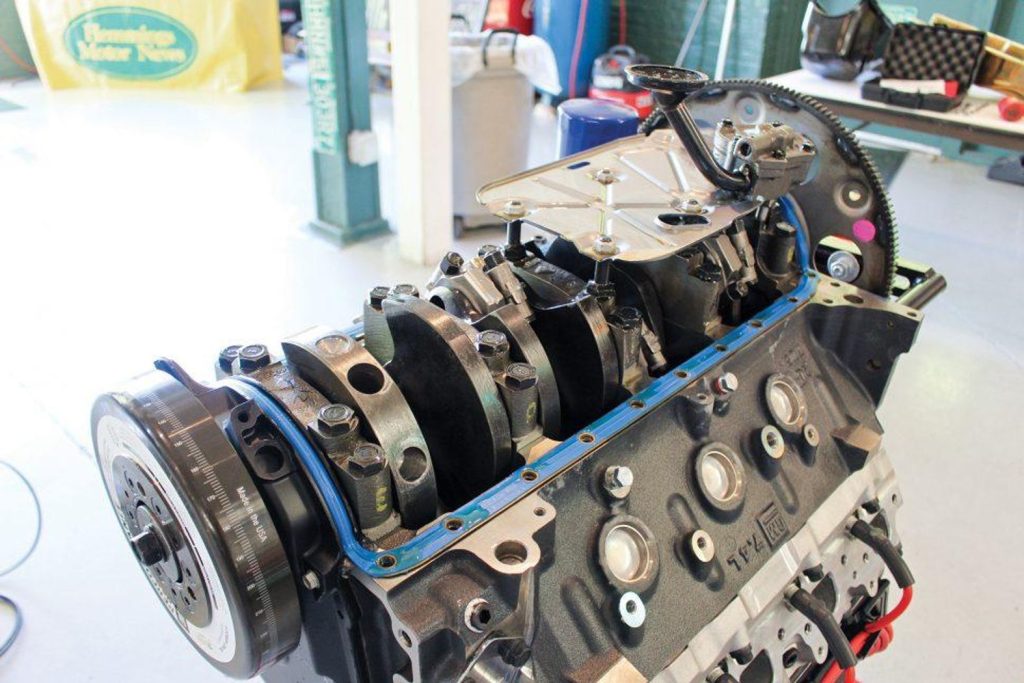

Though the ZZ427 is a traditional Chevy big-block, it is based on a GEN 6 block, which was a revised design introduced in the mid-1990s for use in then-new trucks. The major differences between the GEN 6 and the original Mark IV are the use of a roller hydraulic camshaft and the one-piece rear main seal. Going to a one-piece rear seal meant that the oil pan had to be revised also, so Mark IV pans do not fit. Since the GEN 6 was never installed in passenger cars by the factory, it ships with a truck pan that will not fit in traditional GM cars.

This hurdle was overcome by the performance aftermarket back in the ’90s, when Milodon created a new oil pan that fit the GEN 6, but also featured a profile to clear the engine crossmember in typical GM cars. Like many Milodon pans, it also has increased capacity with “kickouts” on the sump area, and the kit includes a corresponding oil-pump pickup.

We could have dipped into the 396 to find more power, but we thought there might be a better way. Regardless of how a classic muscle car’s performance strikes you today, there is still the “classic” part to consider—most of us won’t want to treat these cars the way we did years ago. That means we’d rather not start making lots of alterations to the car’s original equipment, for fear of harming its originality and value. This is particularly true for numbers-matching examples.

In our case, we already have the Chevelle, and we’re not in a position to add other muscle cars to the fleet—much like many of you. The objective, then, was to increase this car’s fun factor without doing anything that might permanently hinder its value. The simplest way to do that seemed to us to be an engine swap. Our Chevelle’s 396 may be the original, and it runs as it should, even if it isn’t as hairy as we might like. With a Chevy, where parts are plentiful, we could put our 396 to the side and slip in something bigger and hotter with relative ease. While we were at it, we could also stash the original TH-400 and gain an overdrive gear for more relaxed road touring.

Pulling the stock oil pan from the 427 reveals the four-bolt mains and the factory windage tray. The one-piece rear main seal allows the use of a one-piece oil-pan gasket, which is reusable, though the factory does use sealant at the four corners where the gasket tucks into the timing cover up front and the rear main seal housing at the back. Use a delicate touch to make sure the rubber gasket doesn’t tear at one of the glued corners when pulling the pan.

A BIGGER BIG-BLOCK

Though swaps involving GM’s later-model LS-series of V-8 engines are hugely popular today, we felt our big-block Chevelle should remain just that. So, we started working on plans to round up all the parts needed to build a decent 454-based replacement for our 396, but before long, we found ourselves looking at crate engines. Chevrolet Performance (formerly GM Performance Parts) has been offering brand-new big-blocks for years, including 502-inch variations that are quite popular with hot rodders. We started investigating one of the division’s 454s, but then discovered the ZZ427, a more recent offering that uses a modern GEN 6 7.4-liter (454) block with a crank that yields the magical displacement. CP’s promotional material claims that this engine is “a modern take on the L88,” and since so many hot rodders were swapping over-the-counter L88 engines into their SS 396 Chevelles back in the day, it seemed perfect for our ’69.

However, unlike the L88, the ZZ427 is able to take advantage of a modern hydraulic roller cam with 224/234 duration at .050 and .527/.544-inch lift, working with aluminum oval-port heads and a CP aluminum dual-plane intake manifold topped with a 770-cfm Holley to make 480 hp at 6,000 rpm and 490 lb-ft at 3,800. The engine kit includes the trick cast-aluminum rocker covers to clear its roller rocker arms, and even comes with an MSD-built HEI distributor, an aluminum water pump, and an ATI Super Damper.

This engine should fit right in place of our 396, save for some minor differences between the original Mark IV engine design and the current GEN 6. With a few alterations, we should even be able to make it look a lot like a ’69-vintage big-block.

We’re planning to back the new engine up with one of Chevrolet Performance’s Supermatic automatic overdrive transmissions. The one we’ll be using is based on a GM 4L85E, which is a four-speed unit derived from the TH-400 architecture. It uses a lock-up torque converter and offers significant torque capacity, but it also relies on electronic controls, so we’ll be using one of CP’s stand-alone control units.

We’ll get more into the transmission in a future installment of this series, but this time around, we’re prepping the Chevelle and the new engine as the first steps of our upgrade swap. See below for the work so far, which continues in part 2.

SOURCES:

Chevrolet Performance

800-222-1020, www.chevrolet.com/performance-parts

Milodon

805-577-5950, www.milodon.com

Sanderson Headers

800-669-2430, www.sandersonheaders.com

Summit Racing

800-230-3030, www.summitracing.com

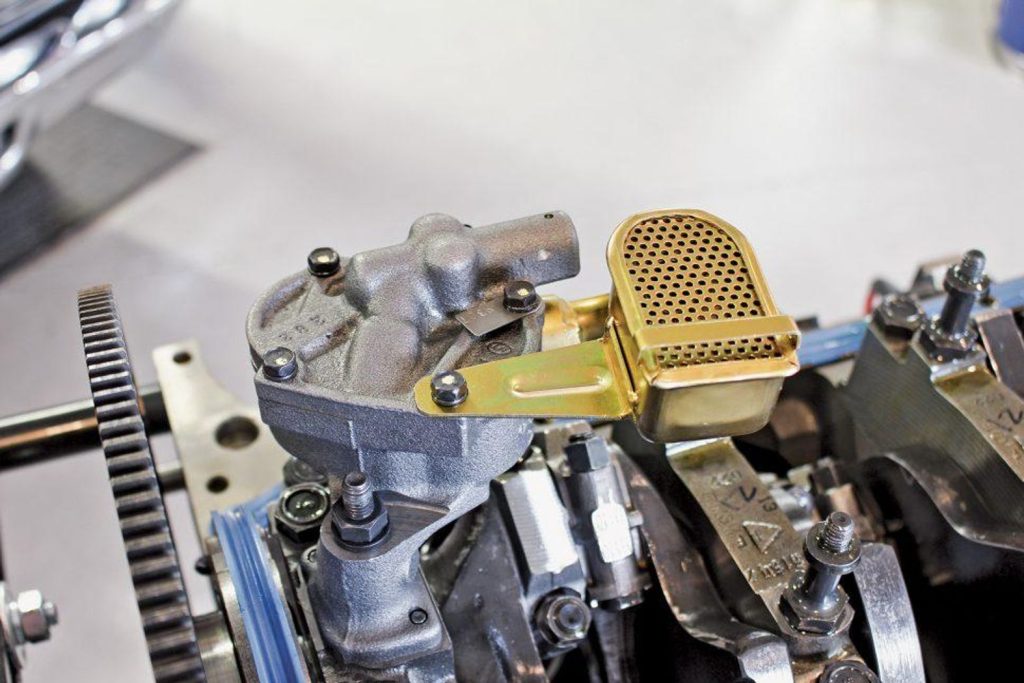

The factory-installed oil pump uses a performance-style pickup, but it will not be positioned to work correctly with the Milodon pan. During assembly, the pickup is welded to the pump—an old racer’s tactic to ensure that the press-fit doesn’t come loose from vibration. To get the old pickup out, we carefully ground off the weld with a Dremel tool, then gently rotated the tube back and forth while pulling it out of the pump.

To install the new Milodon pickup, we used another old trick (which is recommended in the instructions): Place an open-end wrench around the collar of the pickup and then hammer on the wrench to drive the tube into the pump. Hammering on the tube itself could easily damage it.

The Milodon pickup comes with a tab that is intended to be bolted through one of the oil pump’s cover bolts. This provides an alternative means of positively fastening the press-fit pickup tube, so that it doesn’t have to be welded. However, we will need to verify the height of the pickup relative to the pan floor before final assembly. More on that later.

Another component of the GEN 6 big-block that was revised from the Mark IV design is the timing cover, and earlier versions of the newer engines actually came with plastic covers, which were prone to cracking and leaking. But, since Mark IV stamped-steel covers won’t fit the newer engines, Milodon created its own cast-aluminum cover to fit the GEN 6. Our factory cover was a later GEN 6 update, and is also aluminum, as we discovered after taking it off.

To change the timing cover, the harmonic balancer has to be removed. To do this this correctly, especially with a specialty balancer like the ATI unit on this crate engine, a proper balancer puller should be used. Our tool kit came from Summit Racing (and claimed to be made in the USA) and also serves as an installer, which is the configuration it’s in here. Don’t try to drive a balancer back into place with a hammer and a block of wood.

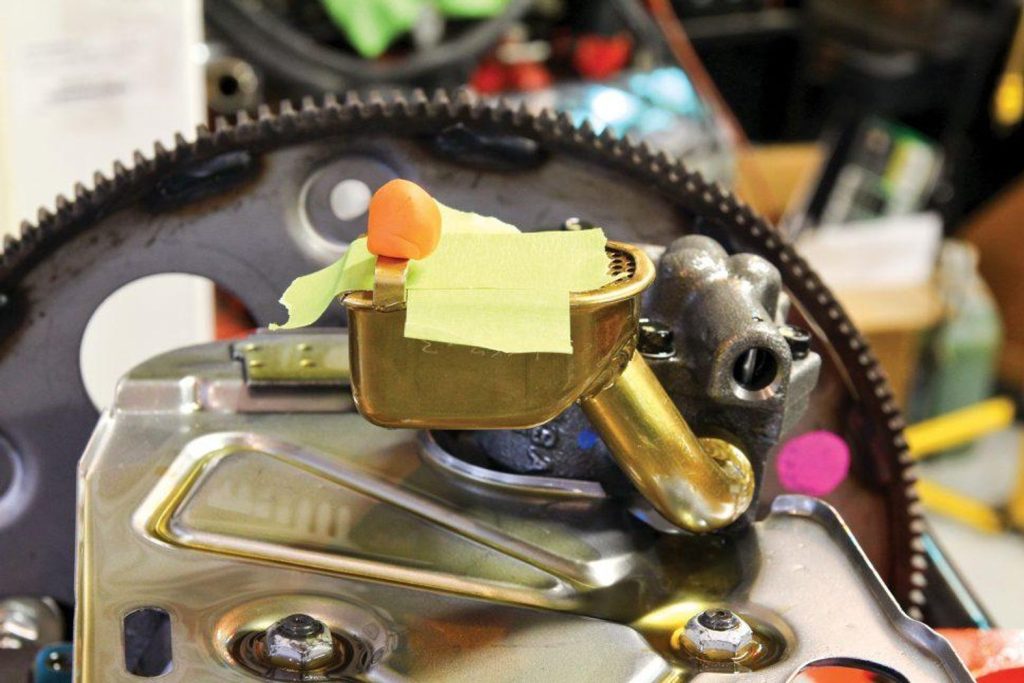

Before installing the new oil pan permanently, it is important to make sure the pickup is properly positioned. The Milodon pickup has a small bar across the inlet screen to prevent it from winding up flat against the pan floor, which would seriously hinder oil flow. However, the instructions advise that this bar should not touch the pan floor, as vibrations transmitted between the two could eventually loosen the pickup. So, we used the standard engine builder’s method of placing a ball of clay on the bottom of the pickup and then bolting up the pan (with its gasket) to see how much it would compress the ball. You’re looking for around 3⁄8-inch clearance, though our first test showed the pickup was actually too high.

With the new timing cover bolted up and the oil pickup height set, we added some fresh sealant to the corners of the gasket and set the Milodon pan in place. You will probably have to jockey the pan’s internal baffle around the pickup to get it to seat. The one-piece gasket has tiny metal tubes in each bolt hole to prevent over tightening.

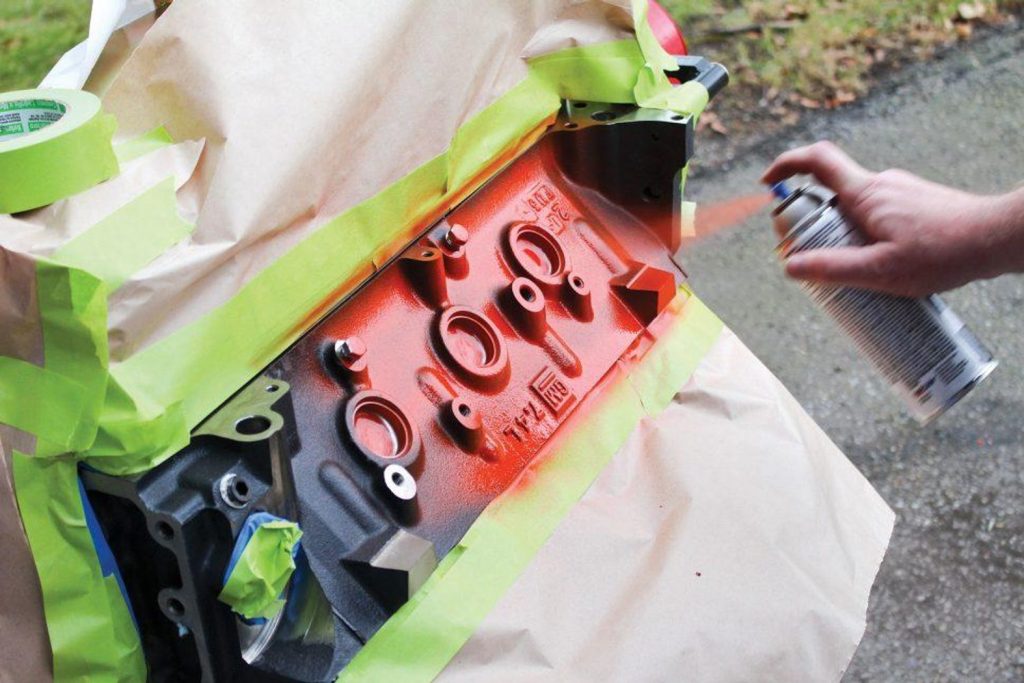

The ZZ427 comes with a black-painted engine block, but we wanted it to look a little more 1969 appropriate, so we wiped it down, masked it off, and hit it with some classic Chevrolet Orange engine paint. There are a number of unpainted spots and threaded holes from the factory, and though they look tidy that way, we sprayed over them during this process, since they will all start to rust very soon otherwise.

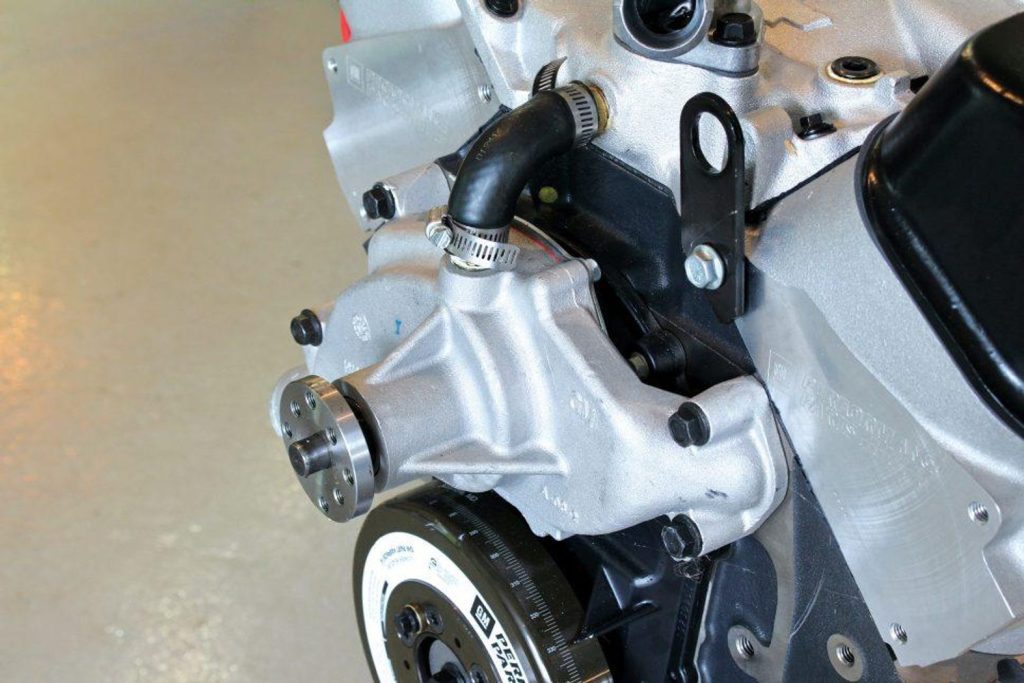

We mentioned that the ZZ427 includes an aluminum water pump, but unfortunately for us, it is of the short-design variety.

Our ’69 Chevelle uses a long-type pump, and since we intend to use factory-style accessories, we needed to stick with that design. Milodon sent us one of its highflow long pumps, which is iron. We test-fit it to make sure the original accessories would fit, but we’ll spray it orange before final assembly.

There’s still a lot to do to get our driveline swap done, but at this point we wanted to test-fit the engine to see how well the Sanderson “3⁄4-length” headers fit the chassis. The “BB3-GEN6” kit is intended for ’68-’72 Chevelles with GEN 6 big-block engine, and we liked the shorter-than-conventional design for the ground-clearance advantage it should offer. We opted for the Silver Ceramic coating, too. One wild card in this hand is the Chevrolet Performance Supermatic transmission we intend to use. It’s based on the GM 4l85E, a truck unit, and it has a larger bellhousing than traditional GM automatics. We’ll delve into that more in the next installment.